Cambridge Seniors: Thelma Leaffer →

Hear Thelma Leaffer’s voice here.

At 83, Thelma Leaffer’s dark eyes light up when she tells stories. Her apple-cheeked face is framed by grey curls which just brush her shoulders. She lives in East Cambridge, in subsidized housing for older people, where she has lived for over a decade. When she lived a few floors below, she used to be close with her floor-mates, many of them immigrants from China. Residents were moved around, and then everyone was restricted to their rooms during the pandemic, so she’s not as familiar with her neighbors anymore. The consolation prize is that her new apartment on an upper floor commands a beautiful view west across Cambridge, and she especially likes catching the sunsets.

Thelma is the daughter of a Ukrainian-American Jewish woman and a Russian-American Jewish man. She was born in New York City, the middle child between an older sister and younger brother. When Thelma was five, her father got a job with Sakorsky Aircraft, and the family relocated to Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Before joining Sakorsky Aircrat, Thelma’s father had quite a storied career. From his teens into his twenties, he was a professional speed-skater on ice. He also performed in a three-person Vaudeville group in New York along with an English couple. He and the other man would ride bicycles onstage and play basketball, while the woman acted as a referee. It was called “Bicycle Basketball.”

Thelma’s beloved Aeroflot (a Russian airline) poster

Thelma’s mother worked in sales, and as an officer in women’s organizations.

As a young woman, Thelma loved music and dancing. She studied the accordion for five years. Her father, having been onstage himself, bought a special white accordion for her which, she remembers, cost $500.00. Her accordion teacher, a professional straight from Italy, had connections in New York City. He finagled getting a recital for his students at the famed Carnegie Hall. When the lights went down in the house, Thelma remembers smilingly, “the light shone [directly] on my white accordion” in a sea of black ones.

Thelma would also play for her parents’ friends when they stayed at the house. Her repertoire consisted of a lot of Beethoven, some Italian music, and Russian folk songs like, “Ochi Chernye” (“Dark Eyes”).

Thelma went to George Washington University. Soon after graduating from college, in 1960, Thelma moved to New York City. She had been hired by Newsweek. They were hiring a number of college-educated women, whom they assigned menial tasks but also taught “editorial techniques.” Thelma was honing her Russian skills at the time, and would read Russian newspapers during her breaks. She also taught English as a Second Language, specializing in teaching Eastern European students.

She used to go over to the United Nations to catch glimpses of illustrious visitors. When Fidel Castro visited from Cuba in the early 1960s, she ducked under the rope and crept closer to him to catch what he looked like. She also met John F. Kennedy before he became President, and was awed by his humility as he thanked everyone one-by-one for coming to one of his speeches.

Thelma received her Masters in Linguistics and her PhD in Psycholinguistics and Cognitive Science from New York University.

She has lived in a number of places: Washington, D.C.; Maryland; Virginia; Connecticut; and New York. She worked as a consultant to government agencies including the National Institute on Aging. She lives in an apartment with a giant window overlooking the grounds. She often invited older people at the Institute to her apartment for coffee or lunch. She especially liked going to hear Dr. Anthony Fauci speak when he worked there.

Thelma moved to Cambridge to continue consulting, working at Synectics. Inc. and as a strategy consultant at Delta Square Associates. She also advised MIT and Fortune 500 companies on communication strategies, and taught at the MBA program at Rutgers University. For years, Thelma contributed stories to the Cambridge Chronicle.

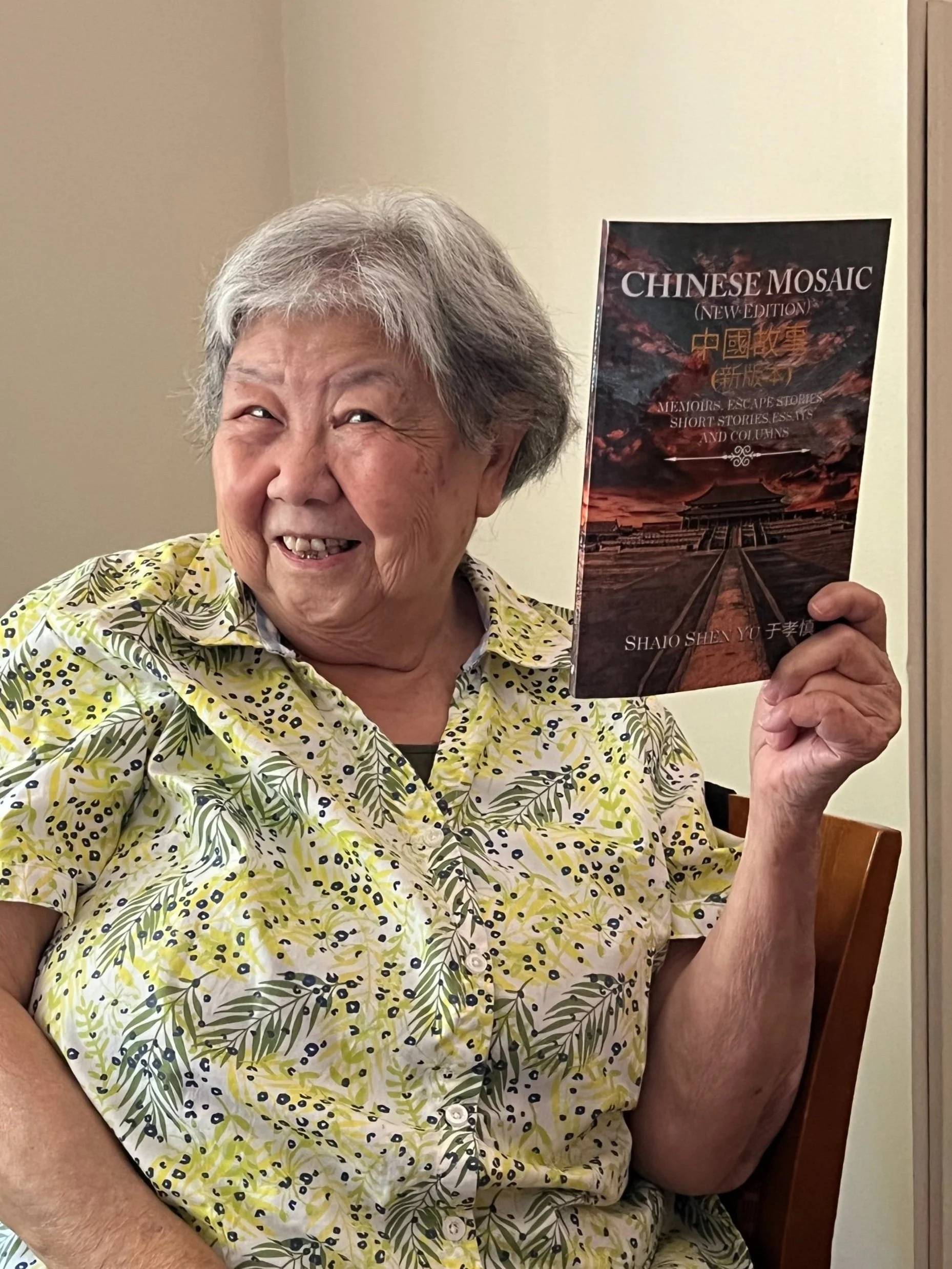

Thelma and her friend, George.

In Cambridge, Thelma became fast friends with a man named George. Every Sunday, George, his friend Ed, and another friend would have brunch together at one of their apartments. Brunching on Sunday was “in” when Thelma lived in New York, and she liked carrying on the tradition. Thelma ended up marrying George’s friend, Ed. She also introduced George and his wife, who had a happy, decades-long marriage.

George died a year ago, and recently Thelma and George’s other friends joined at S and S restaurant in Inman Square to collectively remember him. In her portrait, Thelma is depicted holding up a picture of her beloved friend.